34

MY

ROUSES

EVERYDAY

MAY | JUNE 2015

the

Culinary Influences

issue

A

quick glance at recorded history makes it abundantly clear

that migration or displacement of a people from their

place of origin, whether due to violent conflict, religious

or economic strife, or even a singular meteorological event, often

leaves a gaping hole in the fabric of the society they’ve departed,

while, at the same time, indelibly affecting the culture of their new,

adopted homeland. Few areas in America have benefited from

this phenomenon as much as South Louisiana. From French and

Spanish colonials to Acadians, from Isleños to Sicilians, from

Scots and Irish to Eastern European Jews, and, in the last few

decades (especially since Katrina), large numbers of Latinos from

all over Central and South America, we’ve seen wave after wave of

immigrants settle in these parts and bring with them, among many

other wonderful additions to our cultural melting pot, foods and

cooking techniques from their native lands.

Beginning in the early 1970s, thousands of Vietnamese refugees

fleeing the new Communist regime descended upon Greater New

Orleans, in part because of our

familiar sub-tropical climate,

which provided ideal backyard

growing conditions for many of

the plant foods that are staples

in indigenous Vietnamese

cooking. Many were fishermen

and farmers in Vietnam, and

able to use their skills here on

the Coast.

Most of these immigrants settled either

in the Avondale area of the West Bank or

in “Little Saigon,” near the end of Chef

Menteur Highway in New Orleans East.

Vietnamese restaurants and groceries

quickly appeared, and a Saturday morning

Vietnamese Farmers’ Market followed less

than a decade later.

By the early 1980s, there were more than

15,000 Vietnamese immigrants settled

in Louisiana. Now, generations later, the

number of Vietnamese in Louisiana is

much larger, and the number of Vietnamese

restaurants in and around New Orleans has

exploded.

I must admit that I’m not a particularly

adventurous eater. Fortunately, for guys like

me, it seems as though much like Chinese

restaurants, most Vietnamese restaurants

prepare a variety of somewhat watered

down versions of traditional dishes.

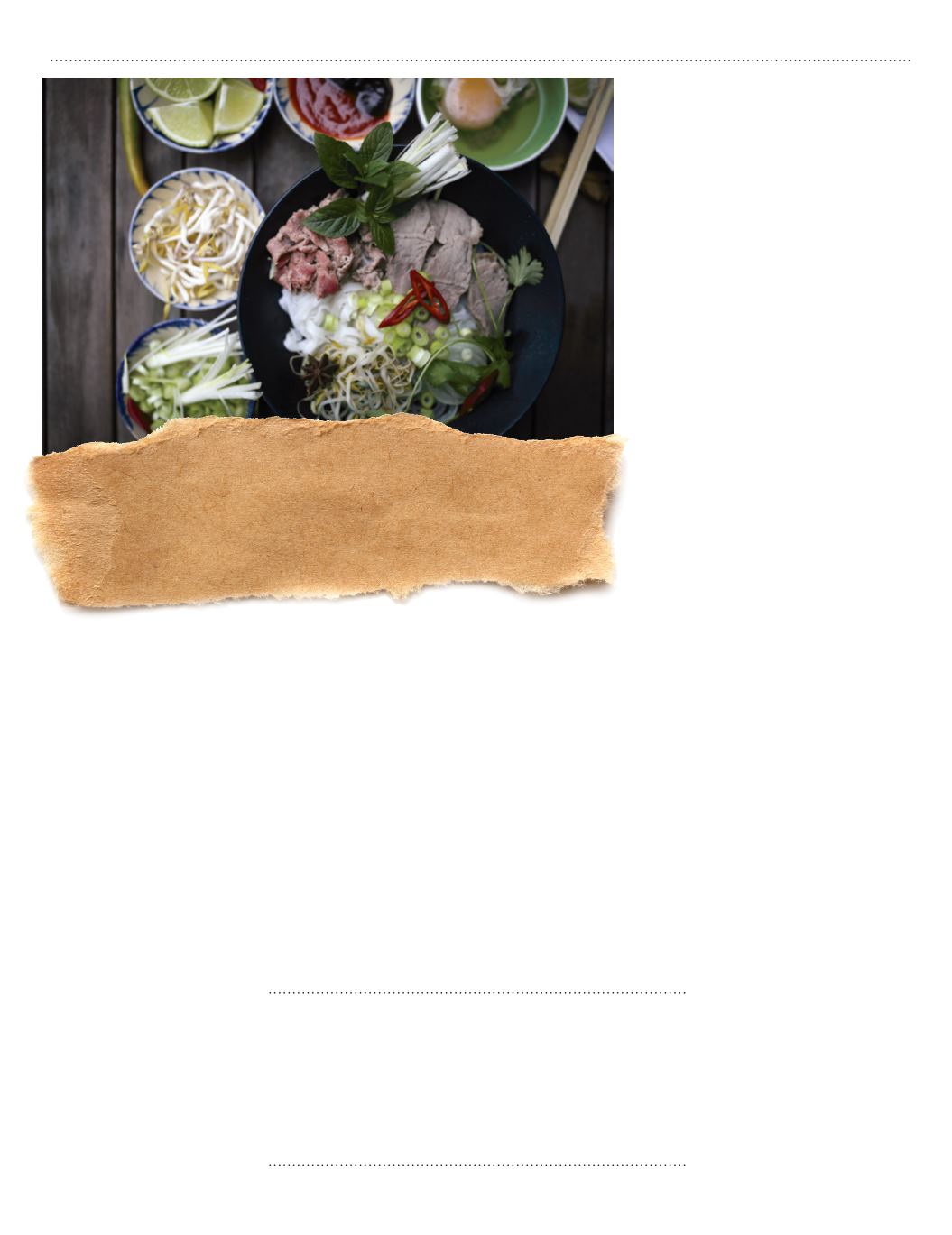

Certainly, one of the most popular dishes

that is readily available everywhere is ph

ở

,

the national dish of Vietnam.

At its essence, ph

ở

is a stock-based noodle

soup with some kind of meat in it — beef

(Ph

ở

N

ạ

m),

is the norm, though Ph

ở

G

à,

with chicken as the protein, has become my

cure for the common cold. Served steaming hot in a large bowl

and accompanied by a basket of fresh additives like basil, bean

sprouts, cilantro, jalapeños and lime, it’s meant to be eaten with

both chopsticks and a spoon. As I understand it, most Americans

do it wrong. We eat the noodles and meat with the chopsticks

and separately scoop the broth with the spoon. Those in the know

apparently use these implements together in one graceful slurp so as

to enjoy all of the bowl’s delicious pleasures at once.

When I asked our editor to arrange a research trip to the West

Bank, she didn’t understand that I was referring to the West Bank

of the Saigon River and, instead, offered me cab fare to Gretna. So

I wound up for lunch at Emeril’s favorite Vietnamese restaurant,

Ph

ở

Tàu Bay. ( John Besh and Anthony Bourdain are also fans.)

The restaurant has occupied the same West Bank location by the

Rouses on Stumpf Boulevard for three decades, but recently lost its

lease, so I was lucky to get a lunch in before the Takacs packed up

for their move to a new location on Tulane Avenue in New Orleans

Bio-Medical District (the new

restaurant opens this summer). I

ordered Ph

ở Đặc

Bi

ệ

t, which is

pho with eye round, brisket and

meatball. For what it’s worth,

tripe and “tendon” are available

for those looking for something

chewy — I don’t do chewy…

To my bowl of pungent, earthy,

slightly oily broth laden with

The word ph

ở

, pronounced fuh, actually refers to the

type of noodle used in the soup — a thin, flat rice

noodle. The way to judge a ph

ỏ

is not by the noodle,

but by the smell and taste of the broth, which is made

with beef or chicken bones and meat, and Star Anise

or Chinese five-spice powder.

east

&

west

by

Brad Gottsegen